Leila Heller, the president of contemporary art galleries in New York and Dubai, happens to also be the author of one of the most beautiful cookbooks released this year.

Titled "Persian Feasts" — and rest assured that the jubilant, convivial recipes inside do indeed live up to that name — the cookbook embraces Persian food and culture in an unabashed manner, tracing the Heller's mother's journey to the US in 1979 as the through-line for Heller's memories.

Full of colorful, fragrant dishes highlighting the stunning breadth of Persian cuisine, Heller bridges the gap between food, art, culture and history in a way that is both inspiring and totally novel.

Salon Food recently had the opportunity to speak with Heller to discuss Persian history, her co-authors, the link between art and cooking, her favorite Persian dishes and so much more.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

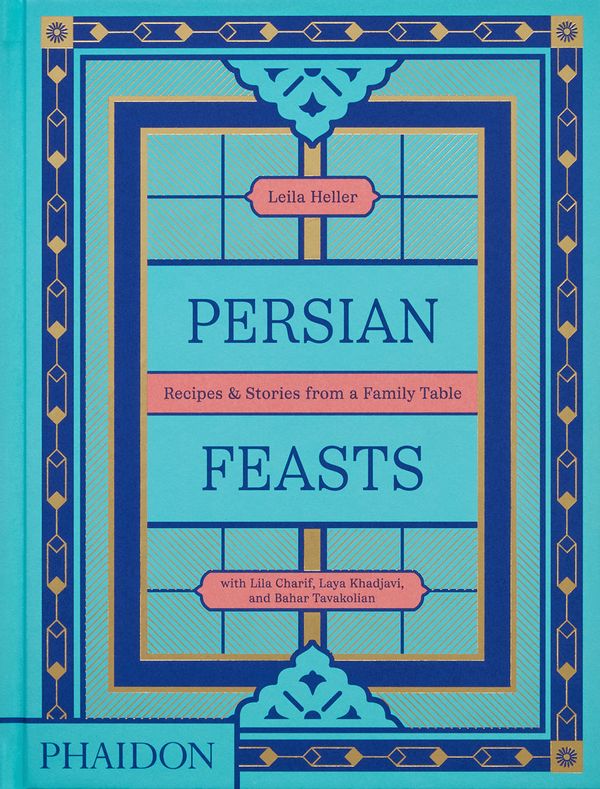

Persian Feasts: Recipes & Stories from a Family Table (Courtesy of Phaidon)

Persian Feasts: Recipes & Stories from a Family Table (Courtesy of Phaidon)

What is your favorite cooking memory?

One of my most cherished memories is cooking alongside my mother when I was just five years old. She had bought me my own set of miniature cooking utensils and pots and I would mimic her every move in the kitchen. This memory is deeply embedded in my mind. Later, as a freshman at Brown University, when the International House invited students to prepare a dish from their home country, I recreated my mother's loobia polo — a fragrant green bean and rice dish with tender veal. I prepared it with the same love and attention to detail as if I had learned the recipe only the day before. The dish was met with great admiration from both the international community and the faculty, who cherished the meal and my enthusiasm.

Why do you cook?

I come from a family where culinary traditions are deeply revered. My mother and grandmother taught me the art of Azerbaijani cooking, a skill passed down through generations. My father's three sisters — Jamileh, Massumeh and Atieh — introduced me to the rich flavors of Russian and Uzbek cuisines, including dishes like borscht, pirozhki and Salad Olivier. This diverse culinary heritage has profoundly shaped my approach to cooking.

What stands out for you as a formative moment that got you into cooking or food at large?

A defining moment in my culinary journey occurred at Brown, where the success of my first dish garnered significant praise. This encouragement led me to cook regularly for fellow students, flatmates and professors, all of whom cherished my cooking. Many saw parallels between my cooking and my visual art — especially my embroidered canvases, which, much like my dishes, were crafted with meticulous care and dedication. After Brown, I continued this tradition in London while pursuing my postgraduate studies at Sotheby's, hosting dinner parties that became a cherished part of my social life. This continued during my time in graduate school in Washington, D.C. and later in New York, where my dinner parties became legendary events, with hundreds of guests in attendance. Today, I continue to cook for every gathering – each meal I serve is home-cooked, reflecting my passion for sharing my food and culture.

Can you tell me a bit about your background in food at large, as well as specifically in regards to Persian cuisine?

I believe that a truly skilled cook can master the cuisine of any culture. I discovered my natural talent for cooking at the age of 18, a gift that runs deep in my maternal and paternal family. I find immense joy in sharing my meals with friends and family, often joking that my husband married me only for my culinary skills. My family, like my parents before us, are food enthusiasts. We travel extensively, not only to experience new adventures but also to explore and savor the diverse cuisines of the world.

Eggplant, Walnut & Pomegranate Stew (Courtesy of Nico Schinco)

Eggplant, Walnut & Pomegranate Stew (Courtesy of Nico Schinco)

What would you say are the foundations or hallmarks of Persian cuisine?

Persian cuisine is traditionally prepared in large quantities and even one family will prepare enough for 5 or 6 people. When cooking for just two, we take great care to prepare a sumptuous meal, typically featuring a pot of rice with a golden, crispy bottom (tahdig), accompanied by a rich Persian stew (khoresh) and sometimes a hearty soup (aash) to begin. Fresh herbs, homemade strained yogurt and pickled vegetables (torshi) are customary accompaniments. For larger gatherings, the table becomes a true feast, with generous servings of rice, various stews, lamb, fish, chicken, duck and an array of appetizers.

The dishes are usually presented buffet-style to accommodate the variety and abundance. Feasting is a long-standing tradition in Persian culture, with its history dating back more than 5,000 years. My co-authors — Lila Charif, Laya Khadjavi, Bahar Tavakolian and I — have titled our book "Persian Feasts" to honor this rich history.

Is there a particular Persian dish that stands out as best exemplifies the cuisine on the whole? Or a personal favorite of yours?

Iran is renowned for its vast array of dishes, including nearly 50 different types of rice and as many stews. One of our most celebrated dishes is chelow kebab, a combination of fragrant white rice with a crispy bottom, served alongside skewers of marinated beef and lamb, roasted tomatoes, peppers, egg yolk and a sprinkle of sumac. This dish is typically accompanied by doogh, a refreshing salty yogurt drink, as well as fresh herbs, feta cheese, walnuts, radishes and strained yogurt, plain or infused with garlic. This would be served with Taftoon, Sangak, or Barbari bread.

What is a great "gateway" recipe in the book for a reader who's totally unfamiliar with Persian ingredients and dishes?

Chelow kebab is a dish that, while seemingly simple, holds great depth and flavor. Another beloved and straightforward dish is abgosht, a hearty stew perfect for the colder months. Our cookbook features two variations of this recipe: one made with lamb and the other with chicken, each offering a comforting and satisfying meal.

So many of the recipes in the book are so beautiful and robust, in both terms of flavor and appearance. Is that typically how Persian food is typified?

Indeed, the presentation of food is of utmost importance in Persian cuisine. The garnishes and embellishments are as significant as the flavors themselves. Iranians take great care in decorating their dishes with slivered nuts, fresh herbs, pomegranate seeds and a delicate sprinkling of spices, as well as caramelized barberries or chopped walnuts, enhancing both the visual appeal and taste.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

This is so much more than "just a cookbook," with historical information, personal and family anecdotes, recipe stories, curated menus and so much more — can you talk a bit about that? What was it like to shine a light on more than just strict recipes?

The recipes in our cookbook were meticulously documented by my mother over a span of 30 years, each perfected with her personal touch. After her sudden passing, I felt a deep responsibility to bring this project to fruition, alongside my dear friends and co-authors, who were like daughters to my mother. I wanted the book to offer more than just recipes; I wanted it to tell a story.

Having been deeply immersed in the art and museum worlds for over 42 years, I reached out to esteemed scholars — Dr. Massumeh Farhad, Chief Curator of Islamic Art at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art and specialist on the 16th century court of Shah Abbas; Dr. Talinn Grigor, an art historian and leading faculty member at the University of California; and Kim Benzel, associate curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art at the MET, as well as MET Museum fellow, Jake Stavis – to contribute essays on the historical significance of food in Persian culture, from ancient times to the modern era. My co-author, Lila Charif, a naturopath, wrote insightful chapters on the health benefits of Persian herbs, spices, oils and teas. I also penned a brief history of my mother’s family, weaving in narratives of Persian feasts and celebrations that are integral to our cultural identity.

Nahid Joon with her children Leila (right) and Mamady (left). (Courtesy of Leila Heller)

Nahid Joon with her children Leila (right) and Mamady (left). (Courtesy of Leila Heller)

For the unfamiliar, can you explain a bit in terms of differentiating between Iranian and Persian cuisine? Or are they one in the same?

Persia and Iran are two names for the same country, though they carry different historical connotations. The name "Persia" originates from "Pars," a region in southwestern Iran and became widely used in the West due to Greek and later European references. It specifically referred to the heartland of the Persian Empire, particularly during the Achaemenid period and has since evoked a sense of the country's ancient grandeur and cultural achievements.

"Iran," however, is rooted in the word "Aryan," meaning "Land of the Aryans," and has been used locally since the Sassanian era to denote the broader realm of the Persian empires. This name reflects a more inclusive identity that encompasses the vast cultural and ethnic diversity of the region. In 1935, Reza Shah Pahlavi formally requested the international community to use "Iran" to better align with the country’s indigenous name and heritage, marking a shift towards a modern national identity that represents all of its people, beyond just the historical Persian heartland.

The adoption of "Iran" was also a statement of sovereignty and unity, embracing the country’s multi-ethnic composition, including Persians, Azeris, Kurds and others. While "Persia" evokes the rich cultural and imperial legacy of the ancient world, "Iran" represents a nation that is dynamic and diverse, with a cohesive identity that honors both its past and its future.

Thus, "Persia" and "Iran" are two sides of the same coin: "Persia" celebrates the historical and cultural richness of a civilization that has profoundly influenced the world, while "Iran" underscores a contemporary, unified nation that reflects its full cultural and historical tapestry. In short, the cuisines are one and the same.

The book is dedicated to your mother, as well as the "brilliant, courageous and brave women of Iran, who inspire all of us." Could you speak a bit about that?

My mother was a true Shirzan (Lion Lady). In Farsi, this term honors women who are strong, who stand up for their rights and who are trailblazers—courageous, brave and resilient, much like a lioness. It is a tribute to my mother and to all the women of Iran who have, throughout history, fought for their rights.

Over the last century, these women have managed families, pursued careers and championed equal access to education alongside men. They have valiantly defended their country, culture and values. These are the women who inspire me, women like my mother, whose unwavering determination helped me achieve my goals and who fought not just for her own rights but also for the rights of her family.

There's such a clear passion for Persian food that permeates this book that is nearly contagious! What are some of your absolute favorite Persian flavors?

I love to prepare dishes such as Ash-e-Anar, a hearty soup rich with herbs, pomegranate juice and lentils; Fesenjoon, a luscious stew made with pomegranate molasses, ground toasted walnuts and either duck or chicken — while I typically prefer duck, I often opt for chicken for larger gatherings; Ghormeh Sabzi, a fragrant herb stew with dried lemons, lamb or beef, red beans and an array of herbs; a baked fish dish with large filets of salmon, sea bass, or halibut, served with an herb sauce; and Albaloo Polo, a sour cherry rice dish, one of my mother's specialties. The rice is beautifully colored by the cherries, with a touch of saffron for a golden hue and garnished with slivered pistachios. I often serve this with my mother’s special turmeric chicken, made with thighs and breasts.

My mother also loved pairing Albaloo Polo with turkey for Thanksgiving — her favorite holiday — as it celebrates all cultures and traditions, a sentiment she deeply valued as an immigrant. For dessert, I enjoy serving Sholeh Zard, a saffron and rosewater-infused rice pudding garnished with slivered nuts. These dishes capture my love for flavors like saffron, pomegranate molasses, turmeric, Omani lemons and fresh herbs.

What would you say are your three most used ingredients?

Choosing just three favorite ingredients would be impossible! Hardly a week goes by without using saffron, turmeric, pomegranate molasses, tamarind, cinnamon, or sumac in my cooking. My mother's unique Persian spice blend is a cornerstone in most of my dishes. I also have a deep love for fresh herbs in my salads — coriander, dill, chives, parsley, oregano, thyme, rosemary and many others.

What would you say is the overlap, if you will, between cooking/food and the art realm?

Cooking, to me, is an art form — much like a painter prepares their canvas, a cook prepares a meal with love, creativity and a keen attention to detail. As I mention in the book, I see my mother’s approach to cooking much like a painter’s canvas, where the universality of art and cooking beautifully intertwine.

We need your help to stay independent

For this book, you worked with various collaborators in Lila Charif, Laya Khadjavi and Behar Tavakolian, a list which includes a naturopathic nutritional therapist. How did this influence the recipes?

My co-authors are not just collaborators but also my closest friends, who were like daughters to my mother. They spent years cooking with her, especially as they began their married lives, often visiting her to learn and refine their recipes. My mother was an extraordinary chef, celebrated for her culinary skills. Lila Charif, Bahar Tavakolian and Laya Kadjavi, whose mothers and mothers-in-law were also close to mine, drew much inspiration from her in their own cooking. Lila Charif, a naturopath, was instrumental in ensuring our recipes promoted health and well-being. Her expertise guided us in selecting the right oils and cooking at temperatures that preserve the nutritional integrity of the ingredients.

Persian Feasts author Leila Heller with co-authors Lila Charif, Bahar Tavakolian and Laya Khadjavi. (Courtesy of Hamid Biglari)

Persian Feasts author Leila Heller with co-authors Lila Charif, Bahar Tavakolian and Laya Khadjavi. (Courtesy of Hamid Biglari)

How do you practice sustainability?

Sustainability is a core principle in my approach to cooking. I strive to use locally sourced ingredients whenever possible and I prioritize sourcing from farmers who practice sustainable methods. Additionally, I ensure that leftovers from my kitchen never go to waste. I share them with friends and family and any remaining food is thoughtfully distributed to elderly friends and others in the community.

What’s your biggest tip for cutting down on food waste?

Persian food has a wonderful quality — it remains delicious over time, often tasting even better on the second or third day. There is no waste in my kitchen. I regularly send meals to my mother’s friends who are homebound or unwell. I believe in minimizing food waste by sharing it with those in need, reinforcing a sense of community and care.

Shares