Tape delays. A bribery scandal. A gold medal snatched from under the nose of a snuffly Romanian pixie. These are not the attributes that the brand burnishers of corporate America want us to associate with the Olympic Games. No, what they have in mind is something a bit more rhapsodic. "We envision the Olympic attributes as 'leadership,' 'competence,' 'fair competition' and 'being the best,'" says Joe Carberry, director of corporate affairs for Visa. "And the chief goal of our sponsorship is, obviously, to align those attributes with those of our own brand."

The strategy, Carberry says, is working. Since 1986, when Visa first became a top-tier Olympic sponsor, "an interesting thing has happened," Carberry says. "In focus groups, people now talk about Visa in the same way they talk about the Olympics. They talk about things like leadership, competence and acceptability ... There's been what we call an 'equity transfer.' That, to us, is proof of return on investment.'"

But should it be? Visa's Olympic sponsorship has always made more sense than most, because of its association with a real benefit -- the fact that Visa is more widely accepted than American Express, even at something as big, global and omnipresent as the Olympics. But Visa isn't content to use its sponsorship of the Summer Games simply to convey a product benefit.

The real goal seems to be to align the Visa brand with an abstract set of Greco-Roman values -- leadership, fair play, goodwill among men. In this, it is not alone. Officials of the other major global sponsors also believe that, through an amorphous process of feelings-leak, the spirit of the Summer Games will seep into their own brand. "We have been very excited about our sponsorship," says Julie Davis, a spokeswoman for Bank of America. "We expect tangible, measurable improvements in attribute ratings as a result of our involvement ... Just as you see Olympians as leaders, excelling in their chosen field, consumers will come to see us as leaders, providing a range of innovative financial solutions."

"We know, based on the research we've done, that when you co-brand with the rings, there is a halo effect," says Steve Burgay, vice president of John Hancock Financial Services Inc. "When you join your logo with the rings, your logo is enhanced. We know that for a quantitative fact."

It's not clear how one quantifies an emotional response to a logo, but never mind. It was for this reason, Burgay says, that David D'Alessandro, president and CEO of John Hancock, took to the airwaves during last year's bribery scandal to urge International Olympic Committee president Juan Antonio Samaranch to clean house. "It had everything to do with protecting our business investment," Burgay explains. "Our logic was: If the IOC does nothing, eventually the taint will spread beyond the IOC, and leak into consumer perception of the rings themselves. If that were to happen, the value of our investment would be diminished significantly."

Hancock's apprehension about its investment is understandable. This year, the Games' 11 "global sponsors" paid upward of $55 million each for the right to display the Olympic rings alongside their own swirls, swooshes and orbital crescents -- a staggering sum that doesn't even include the media buy. Sponsors wishing to purchase airtime were asked to pony up $615,000 for a 30-second spot -- a 40 percent increase over what they were charged in Atlanta in 1996. From an advertising perspective, sponsors have been miffed to discover that they have paid more for less. "As a longtime advertiser, we're concerned," says Nike spokesman Scott Reames. "We invested a lot of money in NBC, based on ratings we expected them to deliver. So far, those ratings have not been delivered. They haven't reached anywhere near the numbers they promised ... So we're disappointed. And we're concerned."

Meanwhile, with the XXVII Olympiad poised to go down in history as the Olympics at which the most athletes tested positive for banned substances, the brand builders' goo-goo-eyed view of the Games as a festival of togetherness seems more naive than ever. Rather than associating the rings with corporately minted virtues such as "leadership," "excellence" and "quality," 21st century viewers seem far more likely to associate the Olympic brand with, say, "chemicals" -- hardly a fertile area for equity transfer, unless you are Monsanto. Hence the recent decision by IBM to end its 40-year history as a top Olympic sponsor. "The general cynicism the public has toward all institutions, they now have toward the Olympics," an IBM marketing official told me. "There's just a lot less trust ... The sunny thought that [by sponsoring the Olympics], you get into people's heads in this deep way ... just seems awfully naive."

Of course, there is one unquestionable thing that advertising during the Olympics does accomplish. "Our research shows that people will only consider doing business with an insurance company that is big, reputable and a leader in the industry," says Hancock's Burgay, with some satisfaction. "Those are the 'price of entry' attributes that we need to demonstrate to consumers ... And those are precisely the attributes that our presence in the Olympics helps us establish."

In other words, by advertising during the Olympics, what you've proved in an equity-transfer sense is that you have a whole lot of money. And indeed, it was this message that emerged as the unsubtle theme of this year's crop of advertising. The spots I caught were massively overproduced, crammed full of verdant fields and indomitable oceans and people running with the sweat droplets coming off them in slow motion. "Why not cross?" intones a white-robed child in the Bank of America spots, as he marvels at the Golden Gate Bridge, the Spirit of St. Louis and other putative Bank of America projects. "Why not explore ... Why not triumph?" Why not spend $50 million to tell viewers that the future is ahead of us, the past behind us?

"We all sort of want to be that child who questions," explains a staffer at Bozell Worldwide, the ad agency for Bank of America. "It had to be 'Why not?' because someone had already taken 'Why?'"

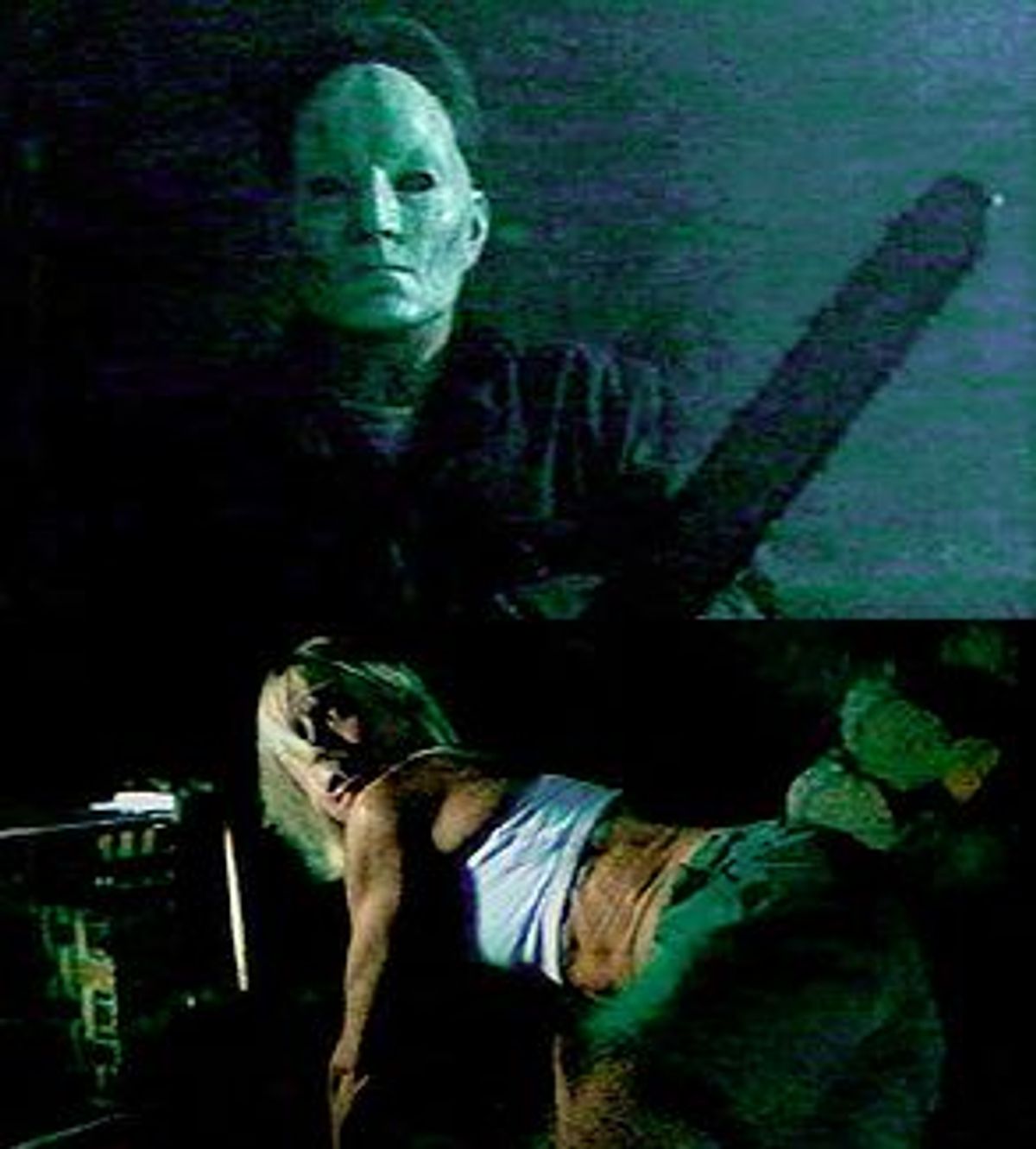

Chain-saw-wielding maniacs, butch pole-vaulters boasting about girly new hairdos, lesbian couples adopting Asian children -- one can see why the question "why?" might have been in high demand. Many viewers were particularly curious in the wake of Nike's chain-saw massacre parody, which featured Olympic runner Suzy Favor Hamilton using her speed to elude a masked pursuer. The ad, which debuted on the third night of the Olympics, was promptly pulled off the air by NBC after viewers protested that it made light of violence against women. Even after the cancellation of the spot, commentators continued to pile on, blasting the ad and denouncing Nike for its insensitivity.

"Stupid ... ill-conceived ... repellent," declared Bob Garfield of Advertising Age. "A far cry from the inspiring and empowering 'Just Do It,'" agreed the Washington Post. On Sept. 19, Stuart Elliott of the New York Times approvingly quoted a reader who labeled the ad "disgusting and misogynistic." At a Women in Advertising awards banquet Wednesday, the ad was again singled out for setting back the cause of women. "The outcry still reverberates," Elliott clucked.

Nike, meanwhile, was left to splutteringly defend itself against the charge of being a woman-hating brand. "This notion that we owe all women an apology is certainly open to conjecture" protests Nike spokesman Reames. "People are going berserk. They're getting really emotional ... They're saying, 'We get this. Nike doesn't.' When the reality is that women are e-mailing us in huge numbers saying, 'I get this. I understand this. I understand what you were trying to do with this ad.'"

Personally, I thought the ad was funny. As Hamilton sprints through the woods, the killer gives chase, vrooming his chain saw in bloody anticipation. Soon, however, he finds he has to stop and rest. He squats on the ground, breathing hard. In his hand, the chain saw whirs uncertainly.

Finally, he whips off his hockey mask and heads home, clearly disgusted with himself. The last shot is of the sneaker-clad Hamilton vanishing into the moonlight. "Why Sport?" the title card asks. "You'll Live Longer."

Whew! While I liked the ad a lot, I don't necessarily disagree with NBC's decision to pull it. The ad is so powerfully shot that it evokes a primal response, thrusting viewers into a visceral experience not of their choosing. (They may have just wanted to watch a little rhythmic gymnastics.) But the shrillness of the response obscures a more interesting, and complicated, issue: the evolving gender politics of Nike advertising. As columnist Barbara Lippert points out in this week's Ad Week, Nike has long employed a double standard in advertising its men's and women's brands. Until quite recently, the ads targeting men were loose, playful and cartoonish, often tweaking or making fun of the very athletes they used as their endorsers. The women's spots, by contrast, were earnest, didactic, issue-oriented: "If you let me play ..."

With the "Horror" spot, however, Nike seems to have stepped down from its soapbox. Hamilton is treated as an athlete rather than as a "woman athlete" who must be self-consciously fawned over and empowered. According to Russell Davis, planning director at Nike ad agency Wieden Kennedy, the shift in strategy is deliberate. "It's one of those things we talk about a lot," Davis says. "There's definitely a shift going on ... At one point, it felt like here was something that needed to be said about women's role in sports. It was all about empowerment, and self-image, and 'if you let me play' ... Now women's sports are higher profile. They've got their own leagues, their own television deals. They're much more on equal footing with men. And the advertising is starting to reflect that."

While not all inequalities have been overcome, "we're now in a position where that empowering, challenging message has become a bit of a clichi," Davis says. "It's become part of the vernacular of marketing ... It's lost its freshness a little bit, especially when used by a brand." As a result, Davis says, "in the last year or so, we've injected a lot more humor, a lot more playfulness, in our treatment of women athletes. We treat Suzy Hamilton pretty much as we would treat Andre Agassi. The ads are fun. They're meant to be humorous ... It's not a role-model, 'go out and be like Suzy' kind of thing. It's more like: We have a bunch of athletes we love, and we want to put them in our communication. End of story."

OK, so it's a bit of a stretch for Wieden to spin a chain-saw-killer ad into a victory for postmodern feminism. Nonetheless, Nike's evolution away from "Our Sports Bras, Ourselves" agitprop seems a milestone worth cheering -- especially when you consider how mired other brands are in the same old first-wave formulas. Consider "I Enjoy Being a Girl," the Visa ad featuring gold-medal-winning pole-vaulter Stacey Dragila. "When I have a brand-new hairdo ... my eyelashes all in curls," the voice-over warbles, as Dragila hoists her body over the bar. Get it? Dragila isn't a stupid girly-girl who wears her hair in curls and has a boyfriend. No, she's a powerful, strong, modern, athletic woman! In the final shot of the ad, Dragila slings her pole vault over her shoulder and walks off into the sunset. "Damn, I'm good!" she says. Quick, get out that chain saw!

While the sneaker company was risking the wrath of whither-feminism colloquies, another, white-shoe advertiser was weathering an Olympic controversy of its own. During the National Gymnastics Championships, John Hancock Financial Services unveiled a spot that was simultaneously hailed and denounced as the first depiction of lesbians in mainstream advertising history. In the beautifully directed spot, titled "Immigration," two stylishly dressed women stand in an airport customs facility, cooing over an Asian infant.

"Do you have her papers?" the blond asks the brunet. "Yeah, in the diaper bag." "The diaper bag -- can you believe this?" says the blond. "We're a family." "You'll make a great mom," whispers the brunet. "So will you."

Of course, John Hancock is hardly the first national advertiser to feature a gay couple in such a matter-of-fact way. Ikea did it years ago, showing a gem|tlich male couple feathering their love nest with inexpensive Swedish furniture. But whereas Ikea was looking to position itself as a young, modern, varied brand for young, modern, varied people, this was clearly not John Hancock's aim. Having used the buzziness of lesbianism as a dramatic device to get attention, the company seemed unsure of where to go next. So it backtracked, implying it had all been an accident.

"It was never our intent to endorse or to dwell on a particular lifestyle," explains Burgay, the company's vice president. Complaints from Christian groups such as the American Family Association convinced Burgay that he "needed to retool the commercial, to help bring the focus on the child, rather than the issue of the child's parents ... We felt we could accommodate people's concerns, and still have a hell of an impactful spot."

Before making its Olympic debut, the ad was recut, with the final lines, which make the lesbian relationship explicit, snipped out. Burgay says the ad agency, Boston's Hill, Holliday, was happy to help. "They understand our business," he says appreciatively. "They understand that, at the end of the day, this is not art. This is a marketing tool ... And if our marketing tool isn't delivering the result we wanted -- then it's time to modify things. They felt very comfortable doing that."

The creative folks at Hill, Holliday, not surprisingly, put it slightly differently. "There are people at this agency who fought really hard to get this made, and who fought really hard to keep it on the air," says one agency staffer. "Now they're tying themselves in knots to be able to say privately that they achieved a triumph ... Of course there were compromises made. But it's still a triumph. We put a lesbian couple on the air in the Olympics adopting a baby."

Soon, however, the spot had to be recut a second time. The Joint Council on International Children's Service protested the ad, on the grounds that it might prompt officials in China, where gay and lesbian adoptions are not permitted, to crack down on single-parent adoptions. So Hill, Holliday went back to the editing room.

"We came up with what we consider to be a very elegant solution," an agency source tells me. "We very artfully ended up adding an announcement, making it clear that they were at the airport in Phnom Penh [Cambodia]. That way we don't adulterate the commercial. And we're sensitive to international adoption agencies in the process."

"So," I say lightly, "I guess Cambodians take a more laissez-faire attitude toward this kind of thing."

"Well," says the source, "we're hoping that takes care of that controversy. But we'll have to see. If issues arise [with the Cambodians], we'll put other solutions under consideration. One solution might include masking the face of the child."

Just as long as it's not a hockey mask.

Shares