Yes, I realize it's tiresome for me to complain about what a bad time I had getting paid to watch movies in the year 2000. So rather than make sweeping general comments about the Year in Film (which sucked, especially for moviegoers in Middle America where Kurdish cinema, et al., was hard to find) I'll just brag on my own personal battle scars.

Between April and August I sat through every second of the following films: "The Skulls," "Ready to Rumble," "Keeping the Faith," "Gossip," "Where the Heart Is," "Battlefield Earth," "Road Trip," "Big Momma's House," "The Kid" and "The In Crowd."

I enjoyed various moments in a few of those movies, especially the ones that were too weird or mean-spirited to draw much of an audience, but I enjoyed them for the same reason that hostages eventually come to identify with the terrorists who feed them weak tea and grilled rat. My only choices were to adapt or perish. In the interest of national unity and healing our partisan divide, I will make no further comments about "Mission to Mars" or "The Replacements," except to concede that only one of them can be the worst movie ever made.

With Hollywood in full retreat into its most conventional mode, old-fashioned art-house filmmaking seemed to blossom in any number of unexpected places. As a child of the '70s who was weaned on high-flown European art cinema and grind-house horror movies, I have no complaints. My top three picks here are all conventional film-critic choices, and despite seeming impossibly disparate all have traditional roots. They'd stand out among the best movies of any year imaginable, and the distinctions I draw between them are simply individual prejudice. (Movies I missed that might have made the list: "Beau Travail," "Before Night Falls," "Hamlet," "Traffic.")

1) "Yi Yi" This is arguably the most ordinary of my top three films, but the characters in the extended middle-class family chronicled here by Taiwanese writer-director Edward Yang have worked their way into my life as if they were my own relatives. Ever since seeing Yang's "The Terrorizer" more than a decade ago at the San Francisco Film Festival, I've expected this Taiwanese writer-director to have an international breakout. If his earlier work seemed under the influence of Luis Buñuel and Bernardo Bertolucci, "Yi Yi" is in a less showy but perhaps more profound mode. In fact, you could call this an adaptation of Ingmar Bergman's "Fanny and Alexander," transposed to contemporary Taipei. A profoundly humane and marvelously pitched drama, it finds romance, pathos, farce, violence and the presence of the sacred within the text of ordinary bourgeois existence.

2) "Dancer in the Dark" Love it or hate it -- and I can sympathize, up to a point, with those who feel the latter emotion -- this agonizing, amazing film establishes Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier as one of the signature artists of our age. Is "Dancer in the Dark" a tragedy or a tragic joke? I can't tell, and I don't know whether von Trier can either. But it's dangerous to assume that such questions have a single, simple answer; to me, "Dancer" has the uncategorizable brilliance of real cinematic magic. There's certainly no cynicism to Icelandic pop singer Björk's heart-wrenching performance as Selma, the blind factory worker willing to sacrifice herself before an incredibly cruel fate to save her little boy, nor to the astonishing musical numbers, written and performed by Björk and shot by von Trier in oversaturated digital video with multiple motionless cameras. On first viewing I felt "Dancer" had a black heart. But another viewer (my mother, actually) convinced me that its vision of 1964 America is really the land of fable, a mythical landscape where Hans Christian Andersen, Thomas Hardy and Franz Kafka would seek moments of redemption amid the shadows.

3) "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" No movie has blended the erotic, spiritual and even feminist elements of the martial-arts genre quite as subtly and graciously as this surpassingly lovely film from trans-Pacific journeyman Ang Lee. That's not the same thing as saying those elements weren't present in abundance, as anyone who has seen Tsui Hark's "Chinese Ghost Story" films can attest. But Lee is not to blame for the fact that American audiences are largely unfamiliar with the tradition from which "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" springs. And even hardcore Hong Kong action geeks will find much to admire in the highflying fight scenes choreographed by Yuen Wo Ping (of "The Matrix" and countless Hong Kong classics). What Lee's huge budget and decelerated pace provide is the opportunity to shoot on glorious Chinese locations as well as in the studio. As in his other movies, which have ranged from Taiwanese gay society to '70s Long Island to the U.S. Civil War, a superb pictorial sense and a contemplative atmosphere ultimately take precedence over plot and action. Stars Chow Yun Fat, Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi are undeniably athletic and compelling, but Lee's film is strongest when he captures them up close, as human beings struggling with the demands of love and duty.

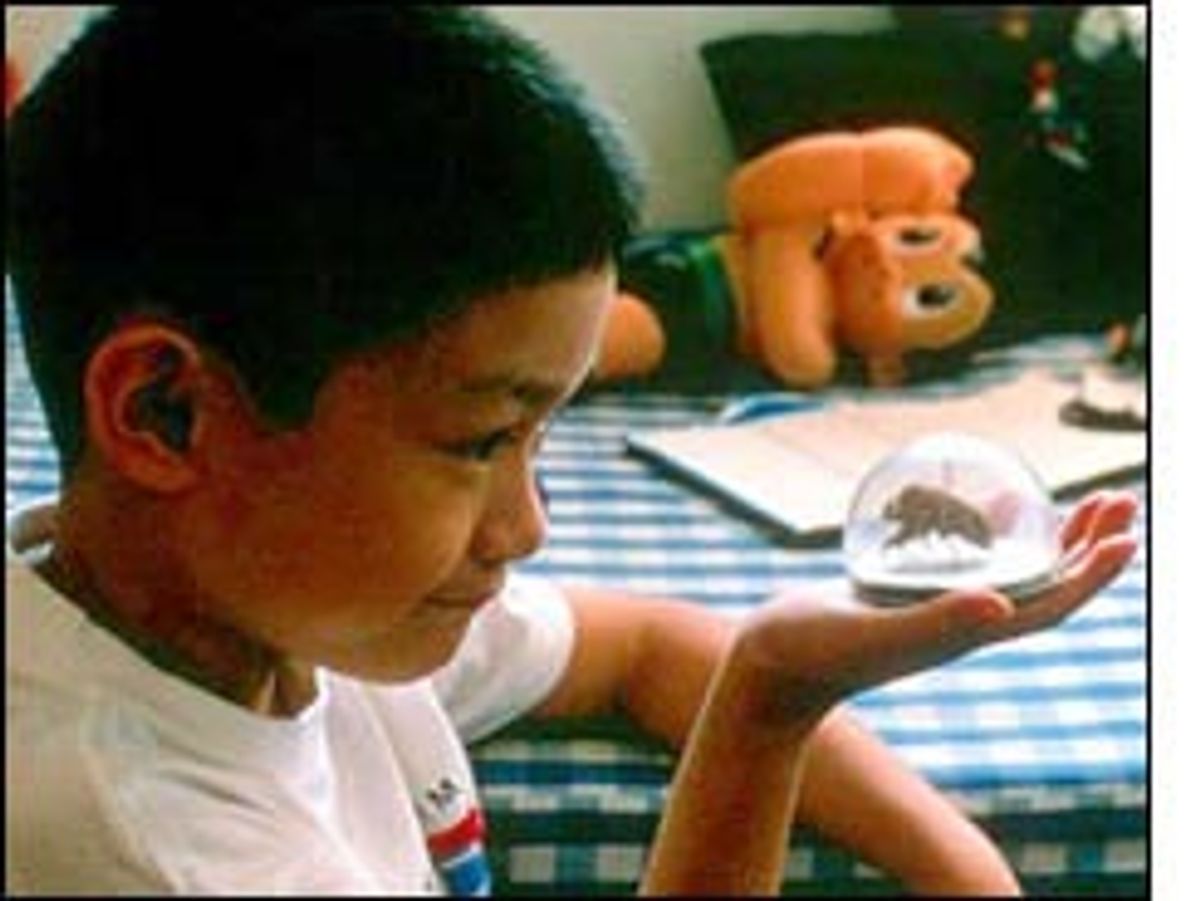

4) "A Time for Drunken Horses" Technically this raw and wrenching work of naturalism was made in Iran, and in fact writer-director Bahman Ghobadi appears as an actor in Abbas Kiarostami's "The Wind Will Carry Us" (see No. 6 below). But "A Time for Drunken Horses" is virtually cinéma vérité, with little of the intellectual meditation that characterizes Kiarostami's films. (Even the title, as viewers of the film will learn, is literal rather than poetic.) Shot in the rugged mountains along the Iran-Iraq border and "starring" a group of local children who essentially play themselves, this is apparently the first Kurdish film to find international distribution. Although it's devastatingly effective as a drama in the Italian neorealist vein -- imagine "The Bicycle Thief" transported to the Near East -- "Drunken Horses" serves a didactic function as well, depicting the isolated and impoverished Kurds as a proud people gradually being crushed by fate and geopolitics. Ghobadi has a tremendous eye for telling sensory detail, and 12-year-old Ayoub Ahmadi, as the boy trying to care for his two sisters and crippled brother, makes in his own way as flawed and noble a hero as Odysseus.

5) "Mifune" If you didn't know that this razor-edged romantic comedy from Danish director Soren Kragh-Jacobsen was made according to the Dogma '95 manifesto (which bans guns, musical soundtracks and all manner of special effects), well, you just wouldn't know, that's all. Although the Dogma decrees have made some critics fulminate, they seem to me essentially a prescription for producing intimate drama in the mode of early Ingmar Bergman and Eric Rohmer. If you're looking for models, you could certainly do worse. There's nothing arty or pretentious about this edgy, likable tale of a Copenhagen yuppie (Anders Berthelsen) who suffers a meltdown right after his marriage to the boss's daughter and escapes to the ramshackle family farm where his father has just died. There he shacks up with his simple-minded brother (Jesper Asholt), a beautiful hooker on the lam (Iben Hjejle, much more at home here than in "High Fidelity") and eventually her misfit younger brother (Emil Tarding) as well. Touching and in the end perhaps a teensy bit sentimental, "Mifune" nonetheless never looks away from the enormous pain these evasive characters put themselves through, and its dark comic streak is immensely rewarding.

6) "The Wind Will Carry Us" Perhaps even more frustrating and elliptical than "A Taste of Cherry," the film that finally brought Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami a wide international reputation, "The Wind Will Carry Us" is nonetheless rich with myth and mystery, with glorious landscapes and the apparent ability to suspend time. Kiarostami is decidedly not for everyone; while his films do indeed have stories and characters, they reveal themselves only gradually and never completely. Here a man believed to be an engineer arrives in a beautiful remote village and cultivates the locals as he waits for something to happen. In a comic reiteration, we watch him repeatedly pile into his SUV and drive frantically to high ground, cellphone pressed to his ear, in a frantic effort to receive a call from Tehran. (Not that useful information is ever conveyed, it would seem.) Finally a strange, semierotic encounter in an underground cave, and a lifesaving mission, unlock some of the film's secrets. For the tiny minority who care, the fact that most of this astringent, lyrical master's 28 films have been virtually unseen in the West is a powerful reason to remain on the planet.

7) "Chunhyang" Ho-hum; just another epic costume drama with postmodern flourishes adapted from the ancient traditions of pansori, or Korean folk opera. I have no idea if any Western viewers are still brave enough for this kind of thing, but "Chunhyang" is the biggest production in the history of Korean cinema and it's a spectacle of amazing richness and variety. A classic tale of love lost and redeemed, it focuses on the passionate, forbidden affair between an 18th century noble and a courtesan's daughter. But that's leaving out the 8,000 extras, 12,000 costumes and many wondrous sets, as well as the narrator who chants or sings along with the action (sometimes anticipating it) and the moments when the whole thing seems to be a stage play performed for a modern audience. Director Im Kwon Taek may be virtually unknown outside his homeland, but he has made almost 100 films (!) in what some observers have called the world's most avidly movie-loving nation. With "Chunhyang," a window I never noticed before opens; the view is breathtaking.

8) "You Can Count on Me" Mark Ruffalo's performance as the deadbeat brother who disrupts Laura Linney's petit-bourgeois single-mom existence in a picturesque upstate New York town lifts the directing debut of playwright Kenneth Lonergan well above the level of indie family drama. Although Ruffalo seems like a shiftless would-be Kerouac, he makes a surprisingly able surrogate dad to young Rory Culkin, while it's Linney who dives into a disastrous affair with her uptight boss (a memorable supporting role for Matthew Broderick). A whimsical, affectionate and uncondescending portrait of middle-middle American life, "You Can Count on Me" is a bit slight and suffers from some late dramatic missteps. But Lonergan's narrative generosity and eye for detail mostly make up for that.

9) "Time Code" OK, it's basically a gag, a Hollywood soap opera refracted into four camera angles and shot in real time on digital video, with no effects or editing. Call it live theater mixed with surveillance video, and if it ain't great theater it's pretty damn good surveillance video. Of course director Mike Figgis still guides the narrative, turning the audio up or down to focus the viewer's attention on one or another of the four visible images. But the tale of studio adultery and intrigue in "Time Code" is at least as amusing as Robert Altman's "The Player" (and less portentous) and the gag works especially well on video, where you can keep rewinding to see what happened in the three images you weren't watching. I'm not sure this experiment will be long remembered or widely emulated, but it's worth checking out.

10) "Bamboozled" Yeah, it's a mess, a withering flame-thrower blast of Swiftian satire directed at anyone and everyone in the entertainment industry, from audiences to executives. But unlike most of my friends I was pretty much convinced by Spike Lee's argument that no one in our culture, black, white or otherwise, is even halfway free of deeply ingrained racist beliefs and stereotypes. Damon Wayans' performance as a buppie TV executive with a fake-o French accent seems way out beyond the outfield fence. Then you realize that Pierre is supposed to be ludicrous, no more a fleshed-out character than Christian Bale's serial killer in "American Psycho." Much of "Bamboozled" is grimly hilarious, like its buffoonish hip-hop band (the Mau Maus) or Michael Rapaport's über-down white boy, and some of it is hallucinatory to the point of incoherence and insanity. Lee would argue that it's an insanity we all share.

Shares