As a director of thrillers, Michael Mann has some peculiar and easily underestimated gifts. The early scenes of "Collateral," in which Jamie Foxx plays a gentle-spirited cab driver who's bullied into driving a hit man (Tom Cruise) around Los Angeles for a night, are edged with enchantment -- and when was the last time you found enchantment in the look of a thriller?

Foxx's character (his name is Max) doesn't seem to be so much driving his cab as guiding it, gondola-like. His L.A. is a city of imaginary canals and rivers, a place where water is in such short supply that it almost becomes a state of mind -- a Venice of moody nighttime blues, of silvery streetlights and Christmas-colored traffic signals.

Max picks up a passenger -- her name, he'll eventually learn, is Annie (Jada Pinkett Smith) -- and they make rickety, exasperated conversation at first, arguing about which route will be fastest. Their standard city-life bickering settles into an easy, conversational camaraderie: Before he drops Annie off, Max learns that she's a prosecutor for the Department of Justice and that the night before she has to present a case (this is one of those nights), her stomach clenches into a knot. Before she leaves Max's cab (and, in an awkwardly flirtatious move, hands him her business card), she learns that his dream is to open his own luxury-limo business. Their differences in class and station are obvious but insignificant: Each gravitates toward the intelligence and candor of the other.

The scene is a dream to watch and to listen to, for the writing and for what Mann and the actors do with it, and for the way its visuals, as in an Edward Hopper painting, capture seemingly contradictory vibes of coziness and isolation. The opening of "Collateral" is everything you want out of the movies in one compact setup: You wonder what else Mann has in store and if anything could possibly top what he's already given us.

But before long, Tom Cruise appears, and you have your answer. "Collateral" is by no means a bad or ineffective movie. It has been put together with thought and care, which used to be standard procedure in the making of thrillers but is now increasingly rare. Yet after that promising start, "Collateral" ratchets down, gradually, to being only average. Mann's visual sense never flags: Most of "Collateral" (its cinematographers are Paul Cameron and Dion Beebe) was shot digitally, using different types of specially modified high-definition cameras, and the picture's surface has an unusual texture: It's somehow crisp and velvety at once.

But the movie's narrative jostles against its visual nocturnal poetry instead of jibing with it. Mann and his screenwriter, Stuart Beattie, wrestle with some big English-lit themes. They're fascinated by the duality of seemingly opposite characters, as well as by our adherence to conventional definitions of manhood. But those ideas aren't folded into the material: They become its reason for existing, and they draw us away from the interplay between the characters instead of into it.

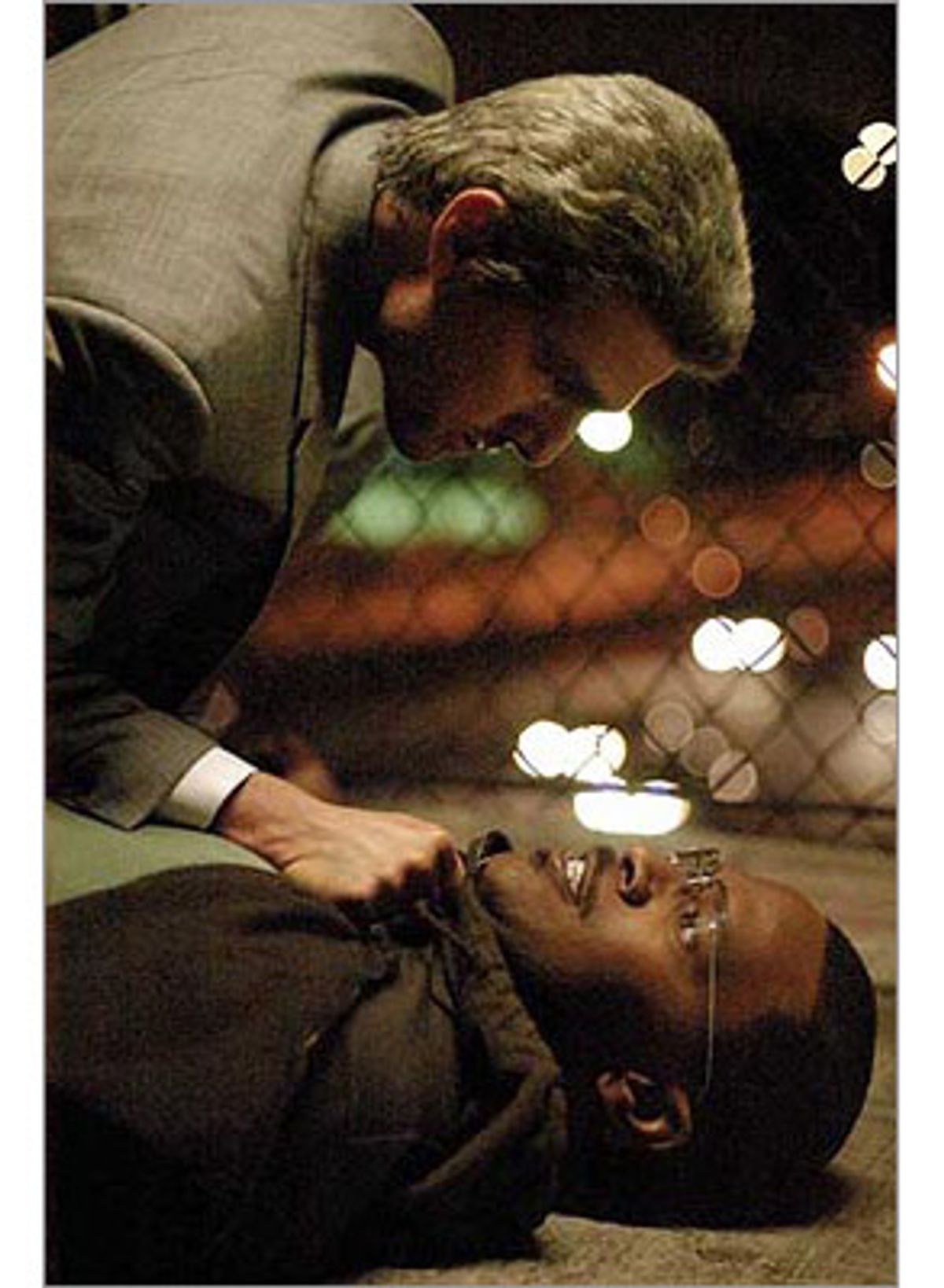

And in many ways, Mann himself is bound by those conventional definitions of manhood. Cruise's character, Vincent, is a smooth professional killer dressed in a shark-colored suit that's almost luminous in the night. His hair and goatee are a grizzled gunmetal color, unusual given his age: This is a man who's seen it all, and yet nothing shows in his face or his eyes -- only his hair is easily shocked. Vincent smooth-talks Max into being his chauffeur for the night (a flash of fanned-out hundred-dollar bills helps) as he goes about the city knocking off various people on his to-do list. Max figures out pretty quickly what Vincent is up to, particularly when Vincent's first corpse crashes from an upper-story window onto the roof of his cab. Max tries to extricate himself from this weird situation, but he can't. He becomes something of a hostage -- or, more specifically, Vincent's collateral.

Vincent and Max spend a good deal of time driving around the city (sometimes with the cops, who include an undercover agent played by Mark Ruffalo) in hot pursuit. Max's elderly mother (played by the always amazing Irma P. Hall) is in the hospital; Vincent not only insists they go visit her -- but also forces Max to bring her a bouquet of flowers. Vincent drags Max to a jazz club, where he spouts a rehearsed hipster spiel about the significance of playing behind the beat. Max is a good guy, smart and quiet and hardworking, vaguely ambitious but probably lacking the gumption to get any serious business venture going. Vincent is a bad guy, but he knows how to get what he wants. The movie asks us to believe that the two are engaged in a symbiotic tussle, each drawing something he needs from the other.

But if you boil the psychology of "Collateral" down to its essence, what you get, mostly, is Vincent badgering Max for not having enough chutzpah -- in essence, for not being enough of a tough guy. And with a character as likable as Max is -- played by a performer as fleet and intuitive as Foxx is -- that just doesn't wash. Cruise works hard at playing Vincent, because he always works hard: His brand of acting, whether you like it or not, seems to grow like a stubborn tree from some old-timey American work ethic, as if acting were just a matter of putting in long, hard hours to figure out how to deliver lines properly.

But Cruise's dignity rings stiff and false (not even the suit helps), and he's no match for Foxx. Foxx inhabits his character so comfortably that he renders meaningless Vincent's babble about the tough, real world. Max is the one who lives in the real world, which is ultimately the point of the movie -- but it takes the picture a very long time to reach a conclusion that's evident from the start to any attuned viewer. Foxx's performance here has nervy wit built right into it -- you don't so much watch him as move with him. And whenever Smith is on-screen (which isn't often enough), she matches him note for note. If we lived in a moviemaking world where the gods smiled down upon charisma and talent instead of getting hung up on gender and skin color, Smith (who was also smashing in Mann's last picture, "Ali") would be a star -- and she may yet become one.

Scene for scene, "Collateral" is nicely crafted. Mann's curse may be that he's a persistently interesting director: Particularly after "The Insider," his finest movie, you somehow want his obvious intelligence to add up to more. (That said, I'll gladly take his slithery, moist-cool "Manhunter" over Brett Ratner's arid, self-serious remake, "Red Dragon," any day.)

The important thing to remember is that he's still capable of surprising us. Somewhere in the last third of "Collateral," around the point where the movie starts to trundle and groan, Vincent and Max, who have been zig-zagging through the streets of Los Angeles, are forced to stop the cab: Several coyotes have come out of nowhere to lope across the street; their eyes catch the light. In just a few seconds they're gone, and neither Vincent nor Max says a word about them. The movie continues, momentarily invigorated by this magical lapse. Why did the coyotes cross the road? Mann doesn't have the answer and, to his credit, he doesn't pretend to.

Shares