Almost 20 years ago Congress ordered Arlington National Cemetery to preserve history, after one of the oldest parts of the burial grounds had fallen into disrepair. That forlorn group of several thousand graves, called Section 27, holds the remains of thousands of Civil War troops, including African-Americans who served with the U.S. Colored Troops, as well as thousands of freed slaves.

But when then-congressman and African-American history buff Louis Stokes began to visit there around 1990, he found headstones there were falling apart and overgrown with weeds. Prodded by Stokes, in 1992 Congress ordered Arlington to replace the crumbling headstones and organize and preserve the historical burial records for Section 27 so vital history about those buried there would not be lost forever.

Superintendent John Metzler told Congress the cemetery was on the case. Arlington replaced the old, crumbling headstones in that section with new, shiny white marble markers. The cemetery also told Congress that burial records for the area got straightened up and preserved. (Metzler is still the superintendent at Arlington).

A Salon investigation shows that 17 years after Metzler's commitment, the cemetery's cosmetic fixes did little to preserve the history of the dead there, and instead appear to have made matters worse. Salon obtained thousands of internal cemetery burial records for that section, along with the cemetery's own internal grave-by-grave map of the section completed in 1990 just before the cemetery's overhaul began, as well as copies of the old, handwritten burial register of the former slaves interred there back in the mid-1800s. Salon discovered that an unknown number of those new, perfect-looking headstones in the historical section have the wrong names on them or are wrongly marked "Unknown." And at least 500 graves, listed as occupied in the cemetery's own records, have no headstones at all today.

It's impossible to judge the scope of the mess in Section 27 because Arlington's own internal paperwork remains badly jumbled. Salon has uncovered similar burial and record-keeping troubles in newer sections of the cemetery, where veterans and their families are still being buried. The continued problems in Section 27 raise questions about whether the cemetery can adequately address rampant burial problems on its own.

Using those materials, here is just a sample of the kinds of problems in Section 27 two decades after Arlington supposedly fixed it:

- A significant number of graves are unmarked today, according to the cemetery's own records. Salon has obtained the cemetery's own meticulously detailed burial map for that section and for another nearby section, Section 49, drawn up in 1990 just before Metzler started his cleanup attempt in Section 27. All of the headstones in Section 49 are in the ground in the right place as they appear on the map. In Section 27, however, hundreds of graves shown as "occupied" on the map are unmarked today. That map, in fact, shows 5,816 occupied graves in Section 27. There are only 5,303 headstones today. (Salon counted.)

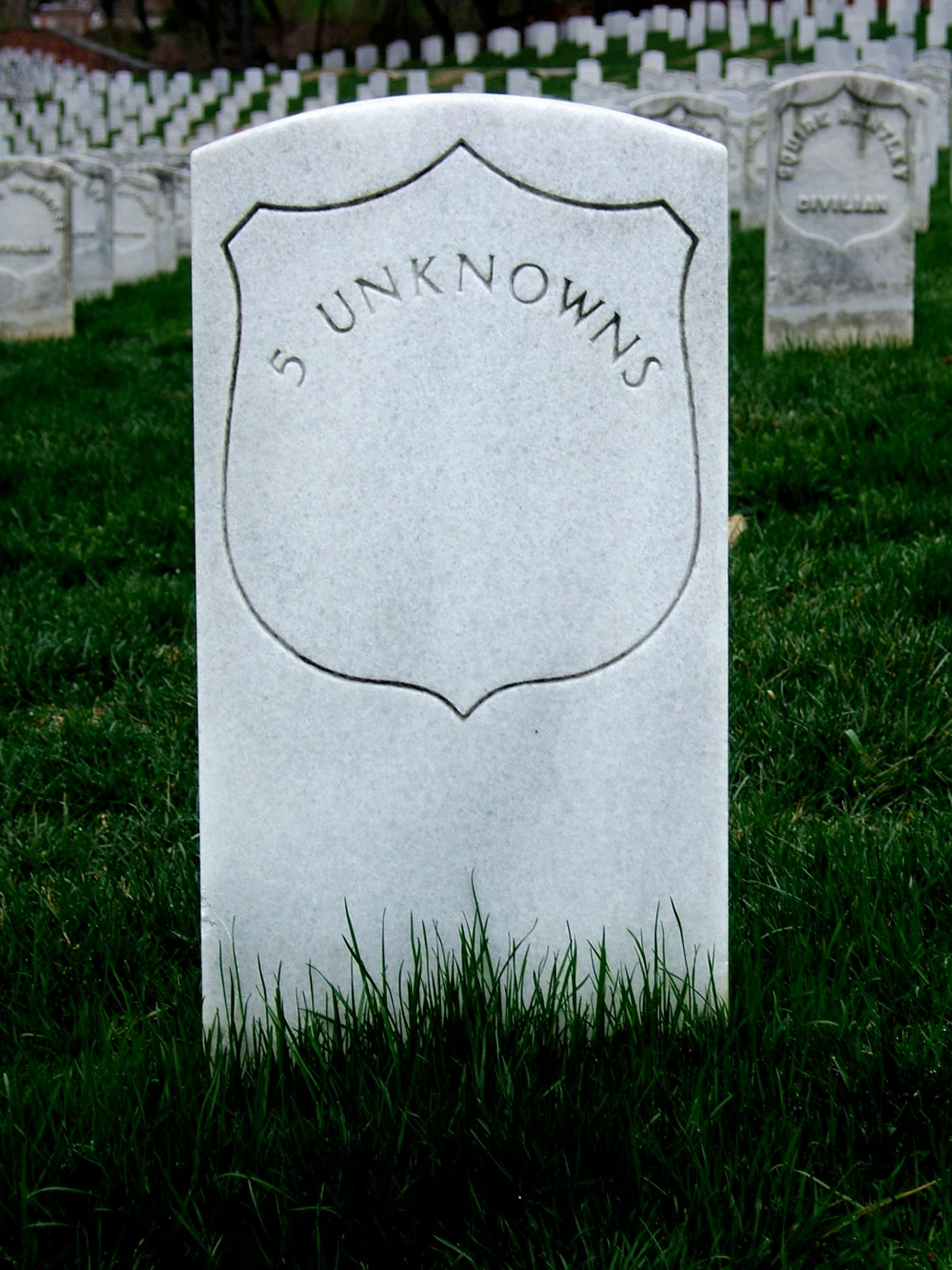

- Some of those buried have lost their identities. According to cemetery records, Robert Taylor died on March 26, 1866; Robert Griffin passed on July 24, 1865; M. Beverly died on May 3, 1865; Lewis Russell passed on April 23, 1866; Pvt. Frederick Armon died on May 30, 1864; and John Jackson passed on June 9, 1866. Their graves are easy to find using the cemetery's own records. The headstones above their graves, however, now read "Unknown." (Note: Salon was able to locate additional records for some of those graves that also read "Unknown." But the names are listed in the old 1800s-era register, showing that those people were clearly buried at Arlington.)

- One person appears to be buried in two places. If you believe the headstones, James Harris is buried twice, side-by-side. Records show one of the Harris headstones is actually above the remains of Moses Ludley, who died on June 27, 1866.

- Some graves are missing headstones entirely. Meredith Hudnell died on Sept. 7, 1864. There is only empty grass above her remains.

Stokes said he was disappointed in what Salon had uncovered there now. "There is still, evidently, a great deal of neglect or even incompetence," Stokes said about the current management of that part of the cemetery. Stokes said he hoped things would improve as a result of this article. "Were it not for you for bringing this to our attention through your stories, this kind of negligence and incompetence would be perpetuated into the future."

Race is central to the story of Section 27. Stokes said the cemetery neglected Section 27, in particular, because African-Americans are predominantly buried there. "I should not have had to have taken the action I did. That was a part of their responsibility," he said about the cemetery leadership. "The only reason that we know of why they did not take the proper responsibility towards that section was because these were black people."

The Army turned down a request for an interview with Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, citing an ongoing investigation by the Army inspector general into other burial fiascoes at Arlington chronicled in prior Salon articles over the past year.

Back in the early 1990s, Stokes was chairman of the appropriations subcommittee that funded the cemetery. Oversight was part of his job. Stokes is also a history buff with a particular interest in African-American history. Section 27 contains the remains of about 1,500 U.S. Colored Troops from the Civil War including Sgt. James Harris, who received the Medal of Honor, as well as the remains of thousands of freed slaves who lived in a settlement at Arlington after the war called Freedman's Village.

Stokes recalled that when he walked those grounds back then he was stunned at what he saw: ancient-looking, decrepit headstones in a state of disrepair and overgrown with weeds. This was in sharp contrast to the pristine-looking rows of white headstones in the rest of the cemetery. "I took an interest because it became clear that this was a neglected part of the whole situation out there," Stokes recalled in a phone interview from Cleveland. "When I got there, I was appalled. It was unkempt," Stokes said. "It was deplorable what I saw out there."

Stokes urged Metzler, the superintendent, to improve things. A review of congressional transcripts from Stokes' subcommittee hearings from that period show the congressman putting significant pressure on Metzler to fix the headstones, clean up and protect burial records, and improve the grounds.

In September 1992, Stokes' subcommittee ordered the cemetery to deliver to Congress a written report on Section 27 describing how the cemetery would "Replace headstones due to the historical significance of the graves in this section," according to the subcommittee's records. Stokes' subcommittee also ordered the cemetery to "Conduct a feasibility study on documenting/recording of the grave sites in Section 27 for historical purposes."

In March 1993, the cemetery sent Congress the report, "Arlington National Cemetery Section # 27 Study." Salon found a copy in the subcommittee's old records. Former Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army G. Edward Dickey wrote the cover letter for the cemetery's report. "The information in the enclosed report updates the committee on activities Arlington National Cemetery is presently undertaking to ensure that the historical nature of Section 27 of the cemetery is properly recognized," Dickey wrote.

The report noted that, "Subsequent to Congressman Stokes' concerns we have redoubled our efforts to ensure that section 27 receives the proper grounds maintenance and care all areas in the cemetery should receive," Arlington reported to the subcommittee.

The report claims that the cemetery had begun to "identify all broken/damaged markers or markers that were no longer legible," the cemetery reported. "Replacement markers have been ordered." The cemetery added that workers had begun to replace the old stones with "marble upright headstones that are appropriately inscribed."

That month, March 1993, Metzler testified before Stokes' subcommittee and said he was making progress in Section 27. "We have started replacing the headstones," Metzler responded to Stokes' tough questioning during that hearing. "We are going to make a concentrated effort to move that program along."

As for the burial records, the cemetery's 1993 report to Congress includes the following: "Included in Arlington National Cemetery's historical holdings is the original handwritten burial register of the U.S. Colored Troops and Civil War Contrabands interred in section 27," the report noted. "This information ... would appear to fulfill the purpose of the feasibility study ... to document and record the gravesites in this section for historical purposes." In other words, the old handwritten register was a key historical document.

In his testimony to Stokes' subcommittee that March, Metzler said he had hired a contractor to restore that burial register and preserve information on who was buried there. Metzler described the contents of the register as precious and said that he would seek advice from experts at the Library of Congress on how to best handle it. "I think one of my concerns is, once we have it restored, that we don't want to have it damaged after its restoration," Metzler told Stokes.

Metzler may have had great concern about damage to that register, but seems to have cared less about the meaning of the contents: people like Moses Ludley, Meredith Hudnell, Robert Taylor, Robert Griffin, M. Beverly, Lewis Russell, John Jackson and an unknown number of other people who are buried under the wrong headstones or no headstone at all.

The continuing problems in Section 27 are also important because the cemetery is about to try to fix a whole new set of burial problems exposed by Salon over the past year. The Army inspector general is conducting a sweeping investigation of burial errors in newer parts of the cemetery -- where people are being buried today -- that were exposed since last summer in a series of Salon articles. Those articles showed unknown remains showing up in supposedly empty graves, accidentally burying one service member on top of another, failure to report problems to families, arbitrarily burying remains as unknowns, etc.

The fact that Section 27 is still far from fixed 20 years later raises serious questions about whether the cemetery can or will fix these new burial problems as well.

Shares