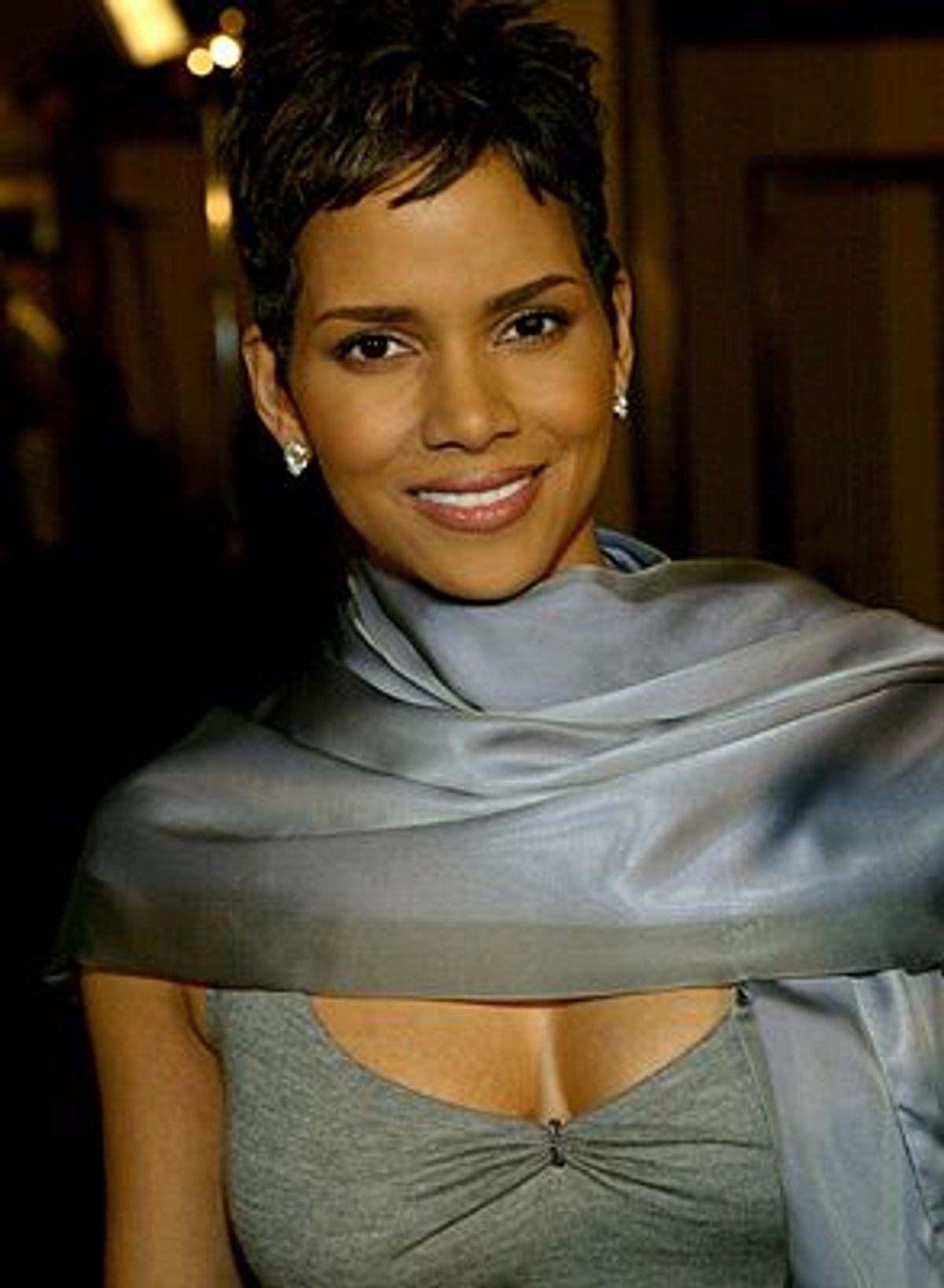

Halle Berry burst into tears as she accepted a Golden Globe award in 2000 for her starring role in the HBO movie "Introducing Dorothy Dandridge," a picture she had produced herself and fought for tirelessly. Starlets' tears are always suspect, particularly at awards shows. Whenever a pretty actress sobs at the podium, she becomes an open target for both critics and the viewers at home: "She's beautiful, she's successful, she just won a prize," the thinking goes. "What's she got to cry about?"

People (a writer for Salon among them) criticized Berry for her tears and her speech, in which she said, "In just five seconds, by announcing my name, hopefully that burden of discrimination will be removed from me. This is for my inner struggle." On its surface, that speech did seem self-serving or at least misguided. But what Berry's critics didn't take into account was that she was a black actress who had just won an award for playing an extremely talented black actress and singer, one who, after being touted as an up-and-coming star, had barely had a movie career and could never have won a major acting award of any kind.

In the 1950s, an era many of us consider ancient history at this point, Dorothy Dandridge tried hard to be a movie star and to reap all the concomitant awards: good roles, big money and top billing.

In 2002, black actresses are still trying.

Maybe you'd cry, too.

Black actors of both sexes have had their problems getting recognized for good work. Part of the problem, of course, is that African-Americans, who make up some 13 percent of the total U.S. population and about 25 percent of moviegoers, are sorely underrepresented in Hollywood, both on the screen and behind the scenes. Sidney Poitier, who will be given an honorary Oscar at this year's awards, was the last black actor to win an Academy Award for best actor, for "Lilies of the Field" in 1963. (That was before we put a man on the moon, and think how long ago that seems.)

Simply put, though, there are more movie stars -- actors who can carry top billing in a film -- among contemporary black male actors than among their female counterparts. Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Eddie Murphy lead the pack; others, like Samuel L. Jackson, Laurence Fishburne, Wesley Snipes, Chris Rock and Martin Lawrence are less luminary but are nonetheless instantly recognizable to most moviegoers.

But does anyone ever refer to "the new Angela Bassett movie"? Does anyone rush out to see new pictures featuring Regina King, Thandie Newton or Nia Long based on those actresses' star power? Worse yet, how many moviegoers actually recognize those extraordinarily talented actresses when they see them? Those actresses and plenty of others remain below the radar of the average moviegoer in a way that Washington and his colleagues do not. In fact, Berry, nominated for an Academy Award this year for her performance in "Monster's Ball," is the first black actress in years to make that kind of mainstream impression. (Whoopi Goldberg, who won an Oscar in 1991 for her role in "Ghost," is a peculiar exception; her reputation rests largely on comedy and she has rarely been allowed to express any kind of romantic or sexual presence on screen.)

There's no shortage of terrific black actresses in Hollywood. So why do we have to look so hard to actually see them in the movies?

At this point I want to address any of you who think I'm simply being an apologist for minorities. Go ahead and accuse me of saying that actors of color should always win awards because of their race and regardless of the quality of their performances (I'm not), or of claiming that actors are always deliberately cheated out of awards purely because of their race (debatable, although not entirely dismissible). Please also feel free to accuse me of condescension: I am, after all, a white liberal making a special plea for a group to which I don't belong.

The truth is that my reasons are purely selfish. The hardest thing about going to the movies for a living isn't sitting through bad movies; it's seeing good work go unrecognized. Anyone who genuinely loves movies and the actors who people them has at one time or another come across a performer and wished to see him or her in bigger, more challenging (or even just different) roles. A few years back, when I wrote about the sad state of contemporary romantic comedies, I offered a list of movie actors I'd like to see paired on-screen. I received several letters asking me specifically (and not belligerently) for more examples of black actors.

Those letters made me realize that many of us (myself included) are guilty of putting African-American actors in their own separate category: They're perfectly acceptable as the stars of glossy, enjoyable comedies like "How Stella Got Her Groove Back" or "Two Can Play That Game" -- pictures aimed specifically at black audiences -- but we're not clamoring to see them in "our" comedies. There's no good reason for that other than cultural conditioning. And while cultural conditioning isn't racism, it's one of the elements that allow it to thrive.

It's important to note that awards mean nothing more than recognition: They can be recognition for bad work that for some reason appeals to the award voters just as easily as for work that's genuinely wonderful. But winning an award does raise an actor's profile, at least for the moment. For that reason, a major award means something different when it's given to an actor who's a member of a racial minority. For better or worse, producers and casting agents pay attention to awards. Berry may not get better roles if she wins the Oscar (it hasn't worked that way for Hilary Swank, after all). But getting a nomination is at least evidence that your colleagues know you exist, and it opens the door a bit wider for you and your contemporaries.

The question of why there are few good roles for black actresses is virtually irrelevant. A more significant question might be: How many roles in Hollywood movies actually need to be played by a white woman, and a white woman only? In a Scripps Howard News Service article written by Dave Mason earlier this year, actress Sherri Shepherd, who had a role in the short-lived TV show "Emeril" and has also made guest appearances on "Friends," explained that there have been days when she'd have just one audition to go to, while the white actresses around her would grumble about having to go to two or three. "I wouldn't say it's discrimination," Shepherd said in the article, referring to the shortage of work for black actresses. "They don't think the part is for an African-American. For a lot of roles, the breakdown is for a white woman. They need to expand their thinking -- maybe an Asian woman, maybe a black woman can play it."

One problem is that there are so few people of color in positions of power in Hollywood. But raising that issue simply raises another question: Why should it take more black power brokers to raise the profile of black actresses? That only lets the existing white studio executives off the hook. Why should they need to have their arms twisted to consider a black actress for a role in which race is of no consequence?

The Hollywood power structure thinks it has a pretty good idea of what audiences will and won't buy in a movie, and it believes that audience standards are fairly rigid and slow to change. But there's no reason even the most conventional minds can't be nudged into more daring territory. Thandie Newton was cast as the love interest opposite Tom Cruise in "M:I-2," a casting choice that Cruise reportedly fought for, to his credit.

Whatever problems audiences may have with interracial romances on film are beside the point. (Very often, in fact, it's black women who object most strongly to them, notably in situations where black men are depicted with white women.) At the very least, the romance in "M:I-2" -- which wasn't presented as an interracial romance at all -- recognizes that in life and in love, we don't always match ourselves up along color lines. Now that one of America's most white-bread movie stars has shown that he's keenly aware of the racial inequities of Hollywood casting, what's everybody else's excuse?

Slowly but surely, we're seeing more interracial romances in the movies, among them the relationship between Nia Long and Giovanni Ribisi in "Boiler Room" (in which the characters' racial differences are never an issue) and that between Berry and Billy Bob Thornton in "Monster's Ball" (in which the characters' racial differences are the whole issue). But even if you view these depictions as small triumphs, they still continue to attract the wrong kind of attention, and from surprising sources. In his recent New Yorker review of Randall Kennedy's book "Nigger," the critic Hilton Als derides the interracial romance in "Monster's Ball," claiming that Berry plays "a white man's idea of black female suffering -- nothing too overwhelming or internal."

Worse, though, is the way Als characterizes Berry's features as "distinctly European." In other words, she's not black enough to count as an official black person. Perhaps he means that audiences would be too shocked by a relationship between a darker-skinned woman and a white man, and thus he believes Berry's casting represents a failure of nerve. But that overly generous reading doesn't even begin to answer the question of why Als himself (who is African-American) stoops to the thinly veiled bigotry of measuring degrees of blackness. If that's his line of thinking, should Lena Horne be considered less black because racist men of the '40s and '50s found her skin light enough to be acceptable in the movies?

With friends like that, black actresses don't need enemies. What they do need, as Shepherd noted, are not necessarily better parts for black women but writers, casting agents, directors and producers who recognize that a range of actresses (regardless of race) could play most parts.

But they also need those power players to pay attention to the roles black actresses have already played and to think of new ways to put them to work. Since the '70s there have been too many such women who have proven their talent only to disappear, almost literally, into the ether. Actresses like Cicely Tyson ("Sounder") and Lonette McKee ("Sparkle") never had the careers they deserved. Their history kept repeating itself, with a succession of other actresses in the starring role, straight through the 1990s. Bassett's portrayal of Tina Turner in the 1992 "What's Love Got to Do with It" was one of the toughest and finest performances I saw by an actress in the '90s. Although Bassett was nominated for an Academy Award (she lost to Holly Hunter for that actress's one-note performance in "The Piano"), has acted regularly in the movies since then (most notably in "How Stella Got Her Groove Back") and is uniformly terrific no matter what the role, she hasn't landed nearly as many major parts as she deserves. She's an actress on par with, say, Jessica Lange; but she never became the star that Lange was at her peak, nor has she earned as much critical attention.

Bassett is the most significant example of a great actress who's been hurt by the color barrier. But if you consider that the movies have room for all kinds of white actresses -- not just Jessica Lange and Sissy Spacek and Michelle Pfeiffer, but also Julia Roberts and Meg Ryan -- then why are there so few berths for black actresses? Regina King has superb comic timing, and she's been wonderful in pictures like "Jerry Maguire," "How Stella Got Her Groove Back" and "Down to Earth." Newton brought as much depth and resonance to the throwaway "M:I-2" as she did to Bernardo Bertolucci's "Besieged." (Luckily, Jonathan Demme has cast her against Mark Wahlberg in his upcoming remake of "Charade.")

Berry is a fine actress who may do better work yet if she hooks up with directors who know how to use understatement to shape a role: Her big scenes in both "Monster's Ball" and "Introducing Dorothy Dandridge" are the weakest and most forced; but when she tosses it all off casually, she's terrific. Most people remember her in the stinker "Swordfish" for her big topless scene; what I remember even more than those exquisite breasts is the way she brazenly (and, I think, knowingly) undercut the gratuitousness of that scene. The look on her face as Dominic Sena's camera lingers on her is a blasi but sexy challenge; it says "Go ahead and look, if that's all you're interested in." (It's also an object lesson in what moviegoers miss when they don't bother to read an actor's expression.)

And what about the actresses who may not have the chops to carry off big, serious roles but whose good looks and charm might carry them a long way with movie audiences? In terms of raw talent, I wouldn't put Vivica A. Fox ("Soul Food," "Two Can Play That Game") or Gabrielle Union ("Bring It On," "Two Can Play That Game") in the same league as Bassett or Berry. But they're beautiful women who, at the very least, have a flirty, vivacious appeal.

And then there are actresses who are too talented for their own good -- or, more specifically, who are too good at things Hollywood just doesn't care about. Vanessa L. Williams is probably still most famous for being a dethroned Miss America (for many of us, that was the thing that actually made her cooler). She's been a sparkling presence in pictures like "Eraser" (opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger) and "Dance With Me." Even in smaller roles, she's a smart, sensitive presence; she should have been poised to get better and better as an actress -- if the roles had been there. What's more, Williams looks sensational, with her apple cheekbones and ice-blue eyes, and can sing and dance to boot. (She's about to open in the Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim's "Into the Woods.") Hollywood has no use for that kind of multifaceted talent; if only that mad genius Baz Luhrmann, one of the few working directors with the guts to attempt musicals, would dream up something for her to do.

There is also a long list of actresses who have shown promise even though they're just getting started or who, even with a good handful of Hollywood roles under their belts, don't seem to be getting the opportunities they should: I'd like to see more and better roles for Nia Long ("Boiler Room," "Stigmata,"), Jada Pinkett Smith ("Ali"), Kerry Washington ("Save the Last Dance," "Our Song"), Queen Latifah ("Living Out Loud") and Kimberly Elise ("Beloved," "John Q."). I'm not much of a Destiny's Child fan, but Beyoncé Knowles might be fun as the next Austin Powers girl. And although you'd think black actresses who specialize in comedy would have an easier time building a career (if Whoopi Goldberg's success is any indication), I'm still wondering when average moviegoers are going to finally start noticing Wanda Sykes ("Pootie Tang" and "Down to Earth"), who takes broad comic conventions and stretches them into some pretty far-out territory.

We can't really predict what's to become of this underappreciated crop of actresses. There is evidence that things are changing for the better: Younger audiences, raised on hip-hop, are more receptive to movies that don't walk strictly defined color lines. (The teen interracial-romance picture "Save the Last Dance" was a huge hit, bringing in more than $90 million at the box office.) Quentin Tarantino resuscitated the career of the fabulous Pam Grier with the 1997 "Jackie Brown," creating a good starring role for a largely forgotten but deserving black actress. (Not to mention that Grier is a knockout reminder of how much sex appeal a 50-ish woman can have.) Tarantino didn't cast Grier simply to make a political statement -- he had always loved her work -- but my guess is that he was also hoping to lead by example.

Hollywood is, unfortunately, slow to pick up on such subtleties. Last spring, People magazine published a report on the status of African-Americans in Hollywood. It was an update on a subject the magazine had first addressed in 1996, and while there have been a few encouraging signs of progress in the past five years, overall the picture wasn't particularly heartening.

That's partly because, to put it bluntly, the same old dunderheads are running the studios, and they show their true colors simply by opening their mouths. The People article noted that studios sometimes claim that movies featuring African-Americans tend not to do well in overseas markets, which is why less money is spent on them in the first place. (To give you a sense of the scale: Berry made $2.5 million for "Swordfish"; Julia Roberts was paid $20 million for "Erin Brockovich.") The article quotes 20th Century Fox studio chairman Tom Rothman saying that African-American dramas like "Soul Food" are "too specific an American experience to be relatable to an international audience."

Surely, that's the voice of genius speaking. Everyone knows that only black Americans are interested in black Americans. (That purely black American art form, R&B, sure turned out to be a dud in other nations of the world, didn't it?) Comments like Rothman's are the purest example of the narrowness of mainstream Hollywood. Could you imagine the same argument being used to keep "Monsoon Wedding" out of American theaters?

My guess is that Rothman phrased his answer as he did because he can't come right out and say that movies featuring black actors aren't profitable -- because it simply isn't true. In its roundup of movie grosses for 2001, Film Comment includes "The Brothers" ($27 million) and "Two Can Play That Game" ($22 million) in the "hugely profitable" category for movies released by indie divisions of major studios. Among major studio releases, "Rush Hour 2" ($226 million) and "Save the Last Dance" ($91 million) were also hugely profitable. And among independent releases, "O" ($16 million) was second only to "Memento" ($25.5 million).

So if the issue is profit in relation to cost, then the Hollywood power elite can't claim that African-American actors can't be cast for financial reasons. And there's no excuse for them to be casting male actors in big movies but not women. Newton didn't keep "M:I-2" from being a big hit, and my guess is that Berry won't hurt the next Bond movie, either.

To say that many of Hollywood's most powerful players are guilty of narrow thinking is an all-too-kind understatement. Mostly, they're not thinking at all. Lena Horne lost the role of the racially mixed Julie in the 1951 "Showboat" to Ava Gardner, who, in the eyes of the studio execs, fit the role just fine; all she needed was a slightly darker shade of Pan-Cake.

Fifty years later, no movie studio would dare such a move: Even the most boneheaded executive would recognize it as racially insensitive. But the invisibility of black actresses is a bigger and more elusive problem. If Hollywood is making movies strictly for so-called Middle America -- for those steadily shrinking patches of the country where one has to drive for miles to encounter a person of color -- then it's not making movies for America at all. Studio execs may look at the numbers all day long. But they still don't see who we are.

Shares